Documenting the Decline of DXPs

A data-driven deep dive: what’s going down, and what might be next

The Digital Experience Platform (DXP) category remains in a precarious state. The original gatekeepers at Gartner recently admitted a cohort of newer vendors from the MACH Alliance to their quadrant as aspirants. Simultaneously, we’ve seen plenty of public commentary about struggles from erstwhile leaders like Acquia and SiteCore. Getting a handle on what’s actually happening can be remarkably difficult.

Analysts do their best to draw conclusions from relatively small amounts of data. They might field a hundred inbound inquiries, or conduct in-depth interviews with tens of decision makers on a given topic as part of producing their research. It’s a valuable pulse on the market, but still not a statistically significant sample.

In my own conversations with practitioners, the prevailing sentiment is that the up-and-coming players are winning, but slowly. Enterprise buyers don’t change platforms overnight — it’s a truism to say that “50% of B2B sales cycles lose to ‘no decision’” — and there are lots of commercial maneuvers that benefit an incumbent vendor, particularly their ability to “run out the clock” on a renewal. All of this tracks, but it’s a very “vibes based” assessment.

I want to fill in that gap, so I turned to the HTTP Archive to bring a data-informed perspective to the state of the market. The HTTP Archive is a public data project that’s been running for well over a decade, dedicated to producing a better understanding of how the web is built. Their annual Web Almanac is a treasure trove of information about what’s going on with the web, gleaned from crawling the 16 million most visited sites on the internet (as reported by Google’s Chrome Real User Experience metrics).

What’s extra special about this project is that they make the raw underlying data available for analysis using Google’s tremendously powerful BigQuery engine. Anyone with their own budget to run queries can crunch the numbers to dig into any particular point of interest within the 80+TB of crawl data, including a whole slew of technographic information, including platform and vendor fingerprints.

I’ve got some budget, and more than enough SQL expertise to be dangerous. BigQuery let me run an analysis that would have taken literal months of processing time on my laptop in the course of an afternoon to generate a large-scale outside-in assessment of the DXP market by the most top-of-funnel metric there is: site count. Here’s what I found:

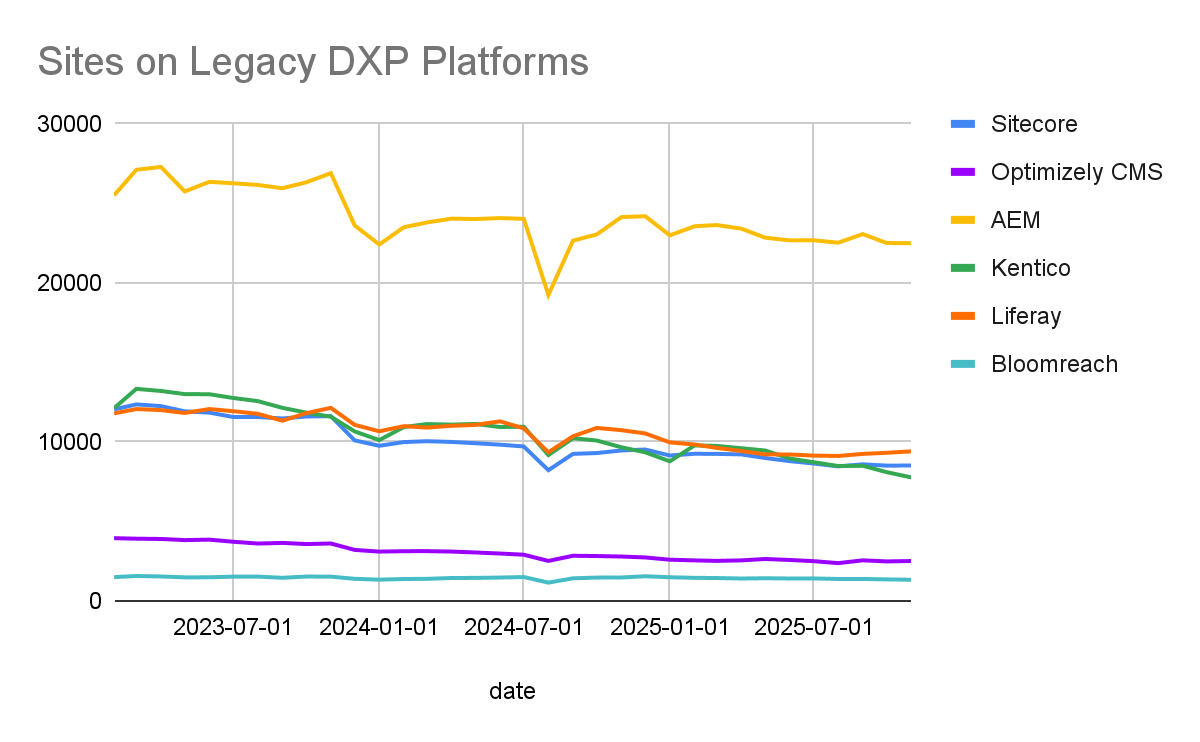

Querying over 1.4 Petabytes of crawl data for the past 34 months shows a remarkably steady picture of decline across all the big DXP vendors. There’s no way to avoid the bare fact: these platforms are directly delivering fewer digital experiences than they were just a few years ago.

Acquia actually fares the best of the original quadrant leaders, with its Drupal-based cloud platform actually adding 1% to its volume. In the same timespan Adobe dropped 16%, SiteCore 30%, and Optimizely a whopping 36%, which we’ll zoom in on below.

What’s the Matter With Optimizely?

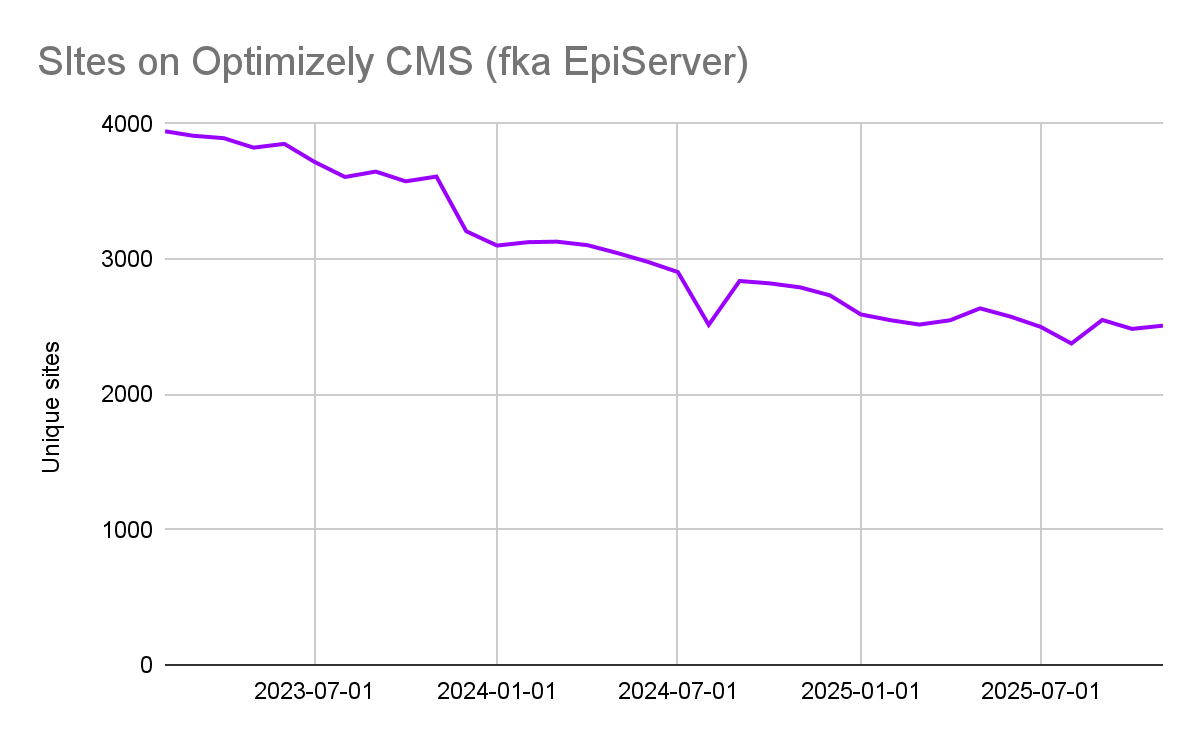

The numbers for Optimizely were particularly surprising given they still retain pride of place in the latest Magic Quadrant. I reached out to my network and got a few different theories. One idea is that their site counts are going down because enterprises are consolidating. Someone else suggested the rise of decoupled front-ends has obscured their true adoption numbers. Those are both valid industry trends, but do they really account for a ⅓ drop in less than two years?

Again, we don’t need to speculate: the data exists to be queried. There are nearly 800 domain names that were powered by Optimizely’s CMS back in early 2023 that don’t fingerprint for that technology today. Only a handful of those (about 40) now run on a modern front-end. A chunk of the old urls (around 100) do redirect somewhere else, which is what you’d expect with consolidation, but in some of those cases the “somewhere else” isn’t running Optimizely anymore.

To be fair, this doesn’t mean their business is tanking. Like the rest of their first-generation DXP peers, Optimizely is an acquisition-based mashup. Their core platform used to be known as EpiServer, but the brand from the acquired A/B testing tool was stronger so they took that on back in 2020. They are also reportedly doing well selling the DAM from their acquisition of Welcome, so perhaps there’s revenue there.

It’s also true that their A/B testing tool is also much more widely used (it’s on over 40,000 sites), but if we’re gauging a platform for digital experiences, core “runs the website” product adoption is a very important metric to track. In my opinion, it’s hard to see a vendor running a few thousand websites as a market leader.

The End of the On-Prem Paradigm

SiteCore has seen a similar decline. One interesting factor for both they and Optimizely is their historic strength in being deeply embedded within the Microsoft ecosystem. That matters a lot if IT has to spec out and manage the infrastructure to deploy the licensed software, but is much less relevant when web technology is (finally) being delivered as a cloud native solution. When a customer isn’t managing infrastructure, the operating system or public cloud vendor doesn’t drive the decision.

Indeed, with the exception of Acquia, all the legacy DXP players are still largely stuck in an “on prem” mode when it comes to their delivery model. Adobe introduced Experience Manager as a cloud service in 2020, but has seen modest adoption. SiteCore famously “self disrupted” by introducing a cloud-native Experience Platform that required a full rebuild to adopt, they’ve since moderated their course.

As an open source company, Acquia became an early adopter of AWS as a platform circa 2010, building their initial product around a managed EC2 service. Today their “Cloud Next” offering uses managed Kubernetes and Aurora DBs to power most of their Drupal sites. Though there are some grumbings about the speed of deployment and the inability to push code changes without risking disruption, this is still as good as if not better than what teams building it themselves with a public cloud can achieve.

The real question is what happens as more teams move further up the stack. While all the DXP players are trending down, Webflow is making serious gains. Their designer-oriented visual builder has grown by over 40% over the time period studied, including among the top million ranked sites, where they now power more sites than any DXP, including Adobe.

The allure of SaaS is real. Acquia is going to market this year with their own “as a Service” version of Drupal, dubbed Acquia Source; ironic given that the delivery model means zero access to any source code. They face that same “self-disruptiuon” risk, as it remains to be seen how much of their current platform customer base will switch over, and how much tension the pivot to SaaS will create with their open source roots.

What’s Next for the Open Web?

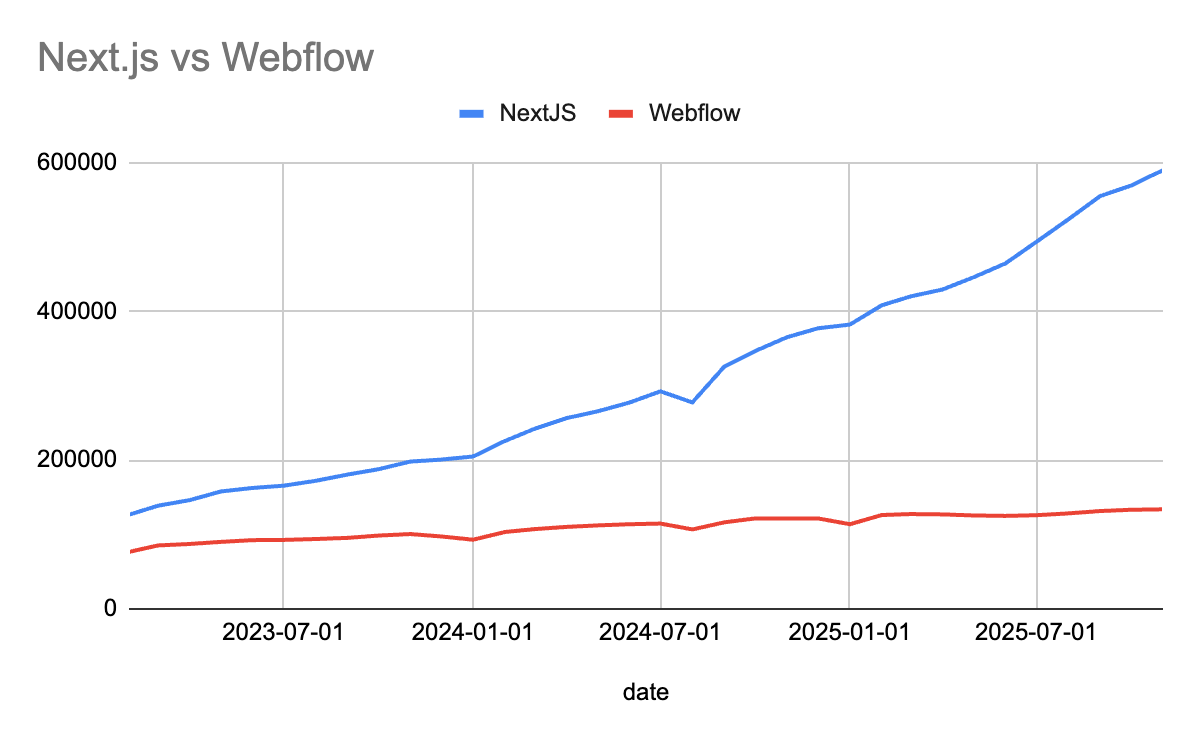

There’s one more standout worth highlighting in the data. Coming in from outside the DXP category and off the top rope, the React-based web framework Next.js has grown a whopping 365% over the time period surveyed. Here they are compared to the aforementioned Webflow:

Keep in mind that Webflow is doing pretty well. They gained 56,000 sites over this time period. But NextJS took over for more than 463,000.

Vercel, the cloud vendor behind the open source project, is riding this growth. They’re running roughly 1 in 3 of these Next.js powered sites, which means two things. First it’s impressive volumetric growth; their tools are being adopted by the rising generation of up and coming web talent. Secondly the fact that two thirds of the NextJS sites are not on Vercel suggests the growth of the framework is on the merits vs driven by their generous freemium model, e.g. not dependent on a VC-fueled unsustainable business model.

It also indicates that the CEO drama about Vercel having some kind of secret sauce or vendor lock-in are more sour grapes on the part of platforms who missed the boat (sorry, Netlify) than a legitimate cause for concern with the framework. Next.js is thriving as an open source/open web framework.

This is by a wide margin the biggest shift from a web technology standpoint over the past couple years. At the moment, analysts categorize Vercel as an Application Delivery Platform, but this feels like it has significant ramifications for the future of the “DXP” category, as well as the wider Open Web. Next.js is the preferred toolkit for a rising generation of web developers, in no small part because it can be used to deliver mobile web experiences that hit the quality bar of native apps.

The way the web is built and delivered is changing, just as the whole business model is being rocked by AI. But while search and ads as a revenue model is being upended, the fundamental utility of the web isn’t going away. Platforms that are a meaningful part of the next era of the web will adapt and innovate. Those that stagnate, or only offer “growth through acquisition” will continue to see their customers point their domains elsewhere over time.